Introduction

The Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C., is the finest Shakespeare collection in the world. Henry Folger established the library because he regarded Shakespeare as “one of the wells from which we Americans draw our national thought, our faith and our hope.”[1] Folger’s interest in Shakespeare was inspired by a short speech he read as a young man by Ralph Waldo Emerson. Emerson argued that Shakespeare was “the first poet of the world,” that he “fulfilled the famous prophecy of Socrates, that the poet most excellent in tragedy would be most excellent in comedy,” and that he is “the most robust and potent thinker that ever was.”[2] Such a judgment was common among educated, and even uneducated, Americans from the earliest days of American independence. Shakespeare became something like what James Fenimore Cooper called him, “the great author of America.”[3] In Walt Whitman’s “maturest judgment” Shakespeare’s English history plays are “in some respects greater than anything else in recorded literature.”[4] Whitman wondered whether Shakespeare did not put “on record the first full exposé—and by far the most vivid one, immeasurably ahead of doctrinaires and economists—of the political theory and results” of a feudal system “which America has come on earth to abnegate and replace.” He speculated that “a future age of criticism . . . may discover in the plays named the scientific (Baconian?) inauguration of modern Democracy.”

—P.P.

[1] “History of the Folger Shakespeare Library,” Folger Shakespeare Library, accessed March 10, 2017, http://www.folger.edu/history.

[2] Atlantic Monthly, A Magazine of Literature, Science, Art, and Politics, (Volume 94, No. 563, 1904), p. 365.

[3] Richard A. Van Orman, “The Bard in the West,” Western Historical Quarterly Vol. 5, No. 1 (Jan., 1974), pp. 29-38, n. 1.

[4] Walt Whitman, “What Lurks Behind Shakspere’s Historical Plays?” Walt Whitman: Complete Poetry and Collected Prose (New York, The Library of America, 1982), 1148 ff.

American Moses*

“I sit with Shakespeare and he winces not. Across the color line I move arm in arm with Balzac and Dumas, where smiling men and welcoming women glide in gilded halls. From out the caves of evening that swing between the strong-limbed earth and the tracery of the stars, I summon Aristotle and Aurelius and what soul I will, and they come all graciously with no scorn nor condescension. So, wed with Truth, I dwell above the Veil.”

W.E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk [1]

Then every thing includes itself in power,

Power into will, will into appetite;

And appetite, an universal wolf,

So doubly seconded with will and power,

Must make perforce an universal prey,

And last eat up himself.

Ulysses, Act 1, scene 3, Troilus and Cressida [2]

In March 1879, an Amherst College senior attended a lecture by Ralph Waldo Emerson in College Hall at Amherst College. The senior, Henry Clay Folger, was inspired by the lecture to read more Emerson, including a short speech Emerson had delivered in 1864 on the tercentenary of Shakespeare’s birth. This reading inspired Folger with a lifelong interest in Shakespeare.[3] Folger went on to become president and chairman of the board of the Standard Oil Company of New York and to marry Emily Clara Jordan (Emily Jordan Folger). Together they studied and collected Shakespeare for the rest of their lives and conceived and provided for the creation of the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C., regarded by informed Shakespeareans as “the finest Shakespeare collection in the world.”[4]

Some lecture. . . . It is an example of the unpredictable and unscriptable way education—teaching and learning—occurs. The teacher presumably has something worthwhile to say, but he can’t and doesn’t know or say it all. There is always more to say and to learn. Maybe some of it has been written down somewhere. The student has his own capacities and inclinations and has to come ready—looking for something important. If you seek, you shall find; but you never know just what you will find or you wouldn’t be seeking. Nor do you know exactly how you will find it, or what the consequences will be. But “all men,” as Aristotle says, “by nature desire to know,” and nature does nothing in vain.[5]

A former classmate claimed that Emerson knew “almost all of Shakespeare by heart” by the time he arrived at Harvard College.[6] Whatever young Emerson knew by heart, he took to heart enough to conclude, in the speech Henry Folger read, that Shakespeare was “the first poet of the world,” that he “fulfilled the famous prophecy of Socrates, that the poet most excellent in tragedy would be most excellent in comedy,” and that he is “the most robust and potent thinker that ever was.”[7] Emerson was registering a judgment similar to that rendered generations earlier by the English poet John Dryden, who wrote of Shakespeare that he was “the man who of all modern and perhaps ancient poets had the largest and most comprehensive soul.”[8]

Such a judgment was common among educated, and even uneducated, Americans from the earliest days of American independence. Thomas Jefferson thought that “a lively and lasting sense of filial duty is more effectually impressed on the mind of a son or daughter by reading King Lear, than by all the dry volumes of ethics, and divinity that were ever written.”[9] John Adams’s diary entry on a Sunday in February 1772 expressed a typical view, regarding Shakespeare as “that great master of every affection of the heart and every sentiment of the mind.”[10] Because Shakespeare was a great master of every human affection and sentiment, he was as Adams later wrote in his Discourses on Davila, a “great teacher of morality and politics.”[11] The judgments Jefferson and Adams made about Shakespeare were rooted in the same understanding of nature and human nature that inspired and shaped the American Revolution. In the divine or natural order of which human beings are a part, it is possible to discern some things that are more beautiful or noble than others, some things more or less just, more or less admirable. In light of such distinctions ascertainable by reason and common sense, one might recognize Richard III as a tyrant and George Washington as a great souled man. The capacity of men to make such distinctions justified a decent respect for the opinions of mankind.

Animated by such an understanding, generations of Americans picked up Shakespeare eagerly to read him, or went eagerly to his plays, in hopes of finding, not just sublime and earthy enjoyment—which they found in abundance—but great treasures from which they might benefit: insights into the most important things in the world, into questions “all men by nature desire to know” more about, such as what is noble or base, what is tyrannical or just, what is good. Because it became so characteristic of Americans to approach Shakespeare in this spirit, he became something like what James Fenimore Cooper called him, “the great author of America.”[12]

The story of Shakespeare in America—of how active, varied, deep, widespread, and continuous has been his presence here—unfolds in colorful episodes that continue to be produced. Early colonial America (especially New England), occupied with taming a wilderness and reading the Bible, didn’t have much use for Shakespeare, though Cotton Mather would purchase a “precious First Folio.”[13] But by mid-18thcentury, one begins to see more regular and continuous evidence of performances of Shakespeare on American stages. Clergymen no less than theater promoters might be heard referring to the “immortal Shakespeare.” There were reports in 1751 of the Emperor and Empress of the Cherokee nation, with some warriors, attending Othello in Williamsburg, and jumping on stage to prevent the violence.[14]

John Quincy Adams, who was born in 1767, wrote of his early and lasting acquaintance with Shakespeare: “at ten years of age I was as familiarly acquainted with his lovers and his clowns, as with Robinson Crusoe, the Pilgrim’s Progress and the Bible. In later years I have left Robinson and the Pilgrim to the perusal of children, but have continued to read the Bible and Shakespeare.”[15] Adams read Shakespeare all his life and saw most of the plays performed. When he served in the House of Representatives, Adams made it a practice to rise at 4:00 a.m. to conduct his private business before turning to his public duties. On the morning of February 19, 1839, he took the trouble in these early private hours to “commune with a lover and worthy representative of Shakespeare upon the glories of the immortal bard,” by sending him a brief but substantial analysis of the character of Hamlet.[16]

Visitors to Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello can still see displayed there a small chip of wood, with this humorous note from Jefferson:

A chip cut from an armed chair in the chimney corner in Shakespeare’s house at Stratford on Avon said to be the identical chair in which he usually sat. If true like the relics of the saints it must miraculously reproduce itself.[17]

Jefferson and Adams visited Stratford upon Avon on April 6, 1786, while their countrymen back home were heading toward constitutional crisis. The only contemporary record Jefferson left of the visit was a note on the price of admission to Shakespeare’s birthplace and tomb. But Abigail Adams many years later added color to the picture. In a letter to her grandson, George Washington Adams, she wrote that “when your Grandfather visited the [spot where Shakespeare was born], with mr Jefferson, [Mr. Jefferson] fell upon the ground and kissed it. Your Grandfather, not quite so enthusiastic, contented himself with cutting a Relic from his chair, which I have now in my possession.”[18] As a young bride, Abigail used to quote Shakespeare quite a bit in her letters to John as he was off putting his life on the line for the Revolution. At some point, in those dangerous days, she took to signing herself Portia.

If Shakespeare was far and away the most popular dramatist in America during the revolutionary and founding years, his influence only grew throughout the 19thcentury. His plays continued to be the most widely performed plays in the relatively sophisticated cities of the east coast, and Shakespeare readings and performances followed as American pioneers pushed the frontier westward. What Alexis de Tocqueville observed in his American travels in the 1830s merely confirms what is known from other sources. Tocqueville found Shakespeare in “the recesses of the forests of the New World. There is hardly a pioneer’s hut that does not contain a few odd volumes of Shakespeare.” A half century after Tocqueville’s visit, a less well known German traveler named Karl Knortz found Shakespeare so influential in this country that he wrote a book about it: Shakespeare in America. “There is, assuredly, no country on the face of this earth,” he wrote, “in which Shakespeare and the Bible are held in such high esteem as in America… If you were to enter an isolated log cabin in the Far West… you [would] certainly find the Bible and in most cases also some cheap edition of the works of the poet Shakespeare.”[19] Shakespeare’s birthplace in Stratford-on-Avon became so popular with Americans as a destination of literary pilgrimages that PT Barnum tried to buy it to remove it to New York. Only vigorous last minute action by patriotic Britons kept Barnum from succeeding.[20]

In the notorious Astor Place riot in 1849, over 20 people were killed and many more injured when thousands of partisans of one (American) Shakespearean actor besieged and invaded a performance of Macbeth by another (British). A couple of thousand miles to the west and a few years later, it is said of Jim Bridger, the famous illiterate scout and mountain man, that he traded a yoke of oxen—worth about a month of his wages as an army scout—to a man on a passing wagon train in Wyoming for a set of Shakespeare. Hiring a German boy for $40 a month to read the plays to him, he memorized many passages and would quote them frequently to people he ran across. Though he couldn’t read, Bridger could speak and understand English, French, Spanish, and several Indian languages. He took his Shakespeare seriously. It is reported that when he found that the two little princes were murdered in Richard III, he burned his set of Shakespeare.[21]

Poet Walt Whitman was at least as serious a student of Shakespeare as was Jim Bridger. Whitman expressed wild and contradictory views on many subjects, including Shakespeare, but despite the murder of the little princes, in Whitman’s “maturest judgment” the English history plays are “in some respects greater than anything else in recorded literature.”[22] In these plays, Whitman sees, unsteadily beginning in the early parts of Henry VI, “as profound and forecasting a brain and pen as ever appear’d in literature.” Whitman would include Coriolanus, Lear, and Macbeth as part of a “whole cluster of . . . plays” that can only be understood by “thinking of them as, in a free sense, the result of an essentially controling plan.” To grasp that plan, to understand in any event its character, Whitman thought one must grasp the unavoidably exoteric, which is to say esoteric, character of all great poetry.

In the whole matter I should specially dwell on, and make much of, that inexplicable element of every highest poetic nature which causes it to cover up and involve its real purpose and meanings in folded removes and far recesses. Of this trait—hiding the nest where common seekers may never find it—the Shaksperean works afford the most numerous and mark’d illustrations known to me. I should even call that trait the leading one through the whole of those works.

Whitman’s “new light on Shakspere” raises the question in Whitman’s mind whether Shakespeare did not put “on record the first full exposé—and by far the most vivid one, immeasurably ahead of doctrinaires and economists—of the political theory and results” of a feudal system “which America has come on earth to abnegate and replace.” He speculates that “a future age of criticism . . . may discover in the plays named the scientific (Baconian?) inauguration of modern Democracy . . . .”

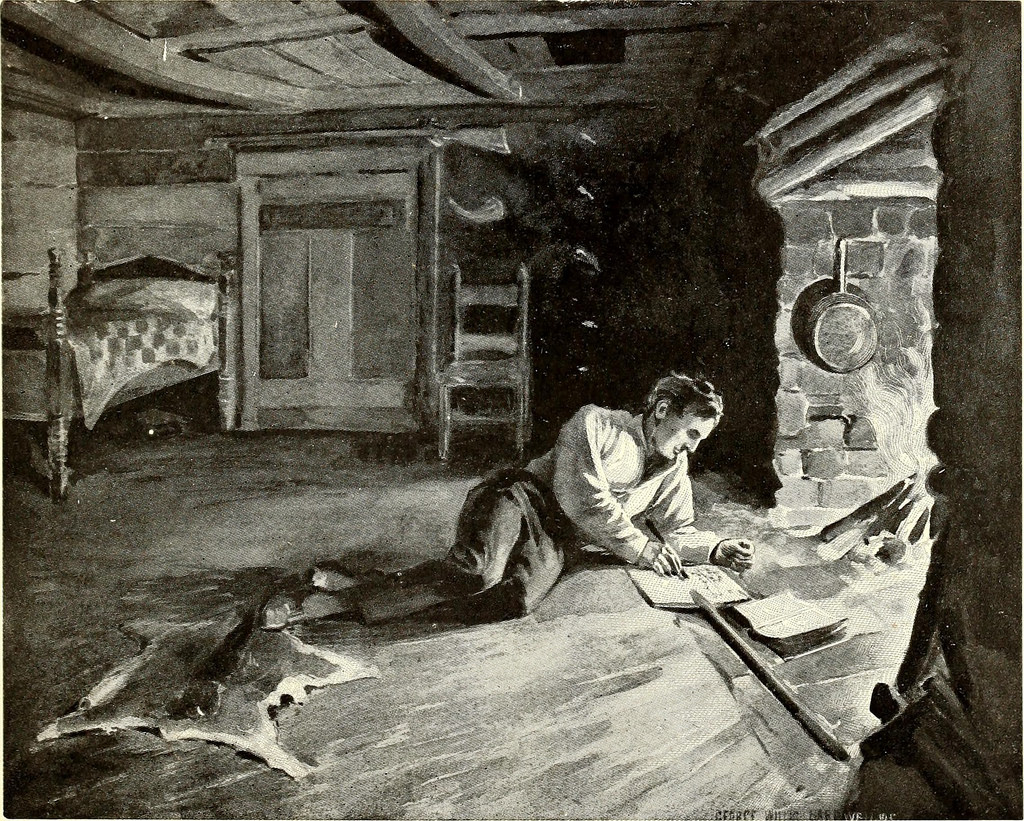

Abraham Lincoln put great stock in reading and writing and taught himself to be a masterful writer and intrepid reader.[23] He read the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, Supreme Court decisions, and political speeches as if his country depended on it, which it did. Shakespeare, he read as if his life depended on it. Like John Adams, he regarded Shakespeare as a great moral and political teacher. He preferred to read aloud, thinking he understood more when the thought came to him through both eyes and ears. There are many stories of him reading Shakespeare in New Salem, Illinois, as a young man and later as a lawyer carrying a volume of Shakespeare with him as he rode circuit. He memorized many substantial passages and was fond of reciting them. By the time he was president, his secretary, John Hay, would report of him that he “read Shakespeare more than all other writers together.” “He would read Shakespeare for hours with a single secretary for audience.”[24] In a letter that would become famous, he even made what he called a “small attempt at [Shakespeare] criticism.”[25]

The classicist and Aristotle scholar Henry Jackson, trying to convey the quality and range of Aristotle’s mind, wrote anachronistically of Aristotle’s Politics, “It is an amazing book. It seems to me to show a Shakespearian understanding of human beings and their ways.”[26] A similar anachronistic compliment might be paid to Shakespeare, that his tragedy and comedy, and even his romance, seem Lincolnian. Lincoln’s soul seems as at home with the inconsolable grief of Richard II, the impossible repentance of Claudius in Hamlet, and the tyrannical temptations of Richard III and Macbeth, as with the outrageous humor of Falstaff. The idea of Lincoln reading Shakespeare for hours on end during the Civil War would remind one of Prospero giving himself to the liberal arts in the Tempest, except that Lincoln never found himself unwisely “neglecting worldly ends.”[27] Among the many colorful ways his fellow citizens expressed their honor and love for Lincoln as his funeral train carried him west to his final resting place, were banners with passages from Shakespeare on them:

Good night! and flights of angels sing thee to thy rest.

His life was gentle, and the elements

So mixed in him, that nature might stand up

And say to all the world – This was a man.[28]

In a short address to the New Jersey State Senate, in Trenton, on his way to being inaugurated president in 1861, Lincoln spoke of Americans as an“almost chosen people.”[29] If Americans are an “almost chosen people,” Shakespeare is almost an American Moses, bringing down from the brightest heaven of invention for every generation of Americans almost sacred tablets of inspired poetry holding the sempiternal promise of leading the American people out of the wilderness and pointing them toward the promised land of a “new birth of freedom.” Thomas Jefferson records that, when writing the American Declaration of Independence, he was attempting to give expression to “the American mind.”[30] In Shakespeare we discover the further reaches of the American soul.

Since Americans assumed their separate and equal station among the powers of the earth, no other poet has so deeply penetrated and thoroughly inhabited the souls of the American people, awakening and informing their sense and sensibilities about every dimension of human experience and speculation—love, tyranny, revenge, virtue, vice, justice, free will, providence, chance, fate, friendship, loyalty, betrayal, passions and reason, men and women, nature and convention, ruling and being ruled, high ambition and low scheming, war and peace, and the vast variety of human characters and regimes.

In his “Defence of Poetry,” Percy Byshe Shelley boasted and complained on behalf of his guild, that poets are “the unacknowledged legislators of the world.”[31] Plato was in full-throated agreement with this sentiment; his Socrates had such doubts about the laws poets lay down that he banished them from his Beautiful City until they could offer a defense of themselves that would probably have to be more rigorous than the one offered by Shelley. The greatest poets, Socrates reflects in Plato’s Republic, are reputed to know “all things human that have to do with virtue and vice, and the divine things, too.”[32] A poet who really did have such knowledge would be most welcome in the Beautiful City, but Socrates hadn’t found one. For most of its existence, the City on a Hill that became America was thought by some of its most thoughtful inhabitants to be providentially or serendipitously blessed with such a poet, or the nearest thing to him, in William Shakespeare.

Henry Folger wanted to establish the Shakespeare library because, as his wife said of him, he believed that “the poet is . . . one of the wells from which we Americans draw our national thought, our faith and our hope.”[33] The Folger Shakespeare Library was dedicated on April 23 (Shakespeare’s traditional birthday), 1932. President Hoover and the first lady presided, and many dignitaries attended. The key speaker was Joseph Quincy Adams (a Cornell University English professor who had been chosen by the Folgers to oversee scholarship at the library and had no relation—amazingly—to the American Adams family). Adams said, “In its capital city a nation is accustomed to rear monuments to those persons who most have contributed to its well-being. And hence Washington has become a city of monuments….[A]mid them all, three memorials stand out, in size, dignity and beauty, conspicuous above the rest: The memorials to Washington, Lincoln, and Shakespeare. . . . The three monuments . . . stand as memorials, and as symbols, of the three great personal forces that have molded the political, the spiritual, and the intellectual life of our nation.”[34]

Not quite a century after the young Henry Folger attended his fateful lecture, another young American student, Stephen Greenblatt, read Friedrich Nietzsche’s On the Genealogy of Morals and was “turned upside down” by it. He later, between undergraduate and graduate school, would study with “the leading English Marxist literary critic at the time,” who would influence “[v]irtually all the work that [Greenblatt did] in the subsequent decades.” In particular, this teacher stirred in Greenblatt an interest in “art’s relation to life,” so that in all his scholarly work he would try to “put the work of art back into the life-world from which it came and to understand its effects upon the very different life-world it may enter, often centuries later.”[35] A little later, as a young professor at Berkeley in the 1970s, Greenblatt attended seminars given by the French thinker Michel Foucault, whom he found “amazing.” “Each sentence was more magical and beautiful than the last.” What Greenblatt thought he learned from Foucault “was the revelation that even something that seems timeless and universal has a history.”“This just seemed fantastically exciting to me, because it meant that things that just seem given are not given, that they’re made up. And if they’re made up that means they can be changed.”[36]

Stephen Greenblatt went on to become the most influential Shakespeare scholar of the late 20th and early 21st century, founder of the school of Shakespeare criticism called the New Historicism. Greenblatt’s approach to the study of Shakespeare attempts to put Shakespeare’s plays back into the Elizabethan or Jacobean “life-world” from which they allegedly came and to consider their effects on or reception in later “life-worlds” in which Shakespeare’s audiences allegedly find themselves. Greenblatt understands himself to be deeply rooted in his own “life-world.” For a while, this was “the world of crazy Berkeley in the 1970s.” More recently he found himself rooted in the milder-seeming world of Harvard in the early 21st century. Whatever world he finds himself rooted in, he tries to bring “the full force of [his] engagement” in it to his study of Shakespeare.

Greenblatt’s approach does not look for insights that might be found in Shakespeare’s plays into things that are “given”—insights into filial duty, for example, or more generally into the distinctions in the dispositions or attitudes of human beings that might be noble or base. The inspiration of Greenblatt’s approach that emerged for him from the crazy world of Berkeley in the 70s is that all such distinctions and attitudes and dispositions are “made up.” For an example, Greenblatt notes the moment in Hamlet in which Claudius is claiming that Hamlet shouldn’t be mourning his father so long, because the death of a father is natural. “This must be so,” Claudius proclaims. One of the great moments of the seventies was the revelation that there is no truth to, “This must be so.”

Presumably Greenblatt does not mean that the death of fathers is “made up.”[37] But dispositions toward fathers and toward death—mourning a father’s death, facing death nobly, fleeing death as a coward—these are made up. So it would be with all dispositions toward life—whether to be generous, or faithful, or honest, or responsible, or the opposites. They are made up somehow—they come as revelations—from the “life-world” from which they emerge. Because there are no “givens” of this sort, because all such dispositions and distinctions between them are made up, Greenblatt brings the energy, passion, conviction, fear, rage, and other dispositions that are made up from his own life-worlds to bear on his study of Shakespeare, and he finds that what makes Shakespeare’s art enduring is precisely that it is “malleable.” It has “its roots in the deepest possible way in [Shakespeare’s] world.” But it is able “to reach out and make itself available to other worlds, including the world of crazy Berkeley in the 1970s.”[38] To be “malleable,” to “make itself available” to other worlds, means to be susceptible to “change” by those worlds. It is not surprising, then, that “new historicists” generally find in the study of Shakespeare occasion for venting the passions, convictions, fear, and rage about racism, sexism, elitism, and colonialism that are “made up” from or revealed by the “life-world” in which they find themselves.

Attempting to liberate himself from the timeless and universal “givens”—nothing is more timeless and universal than God or nature—Greenblatt shackles himself and his followers to the narrow “made up” fears and rages of his own crazy life-world. This cramped view of Shakespeare (and all other authors) could never inspire a lifelong endeavor to understand him and to collect his works. The Washington Folger Shakespeare Library holds 82 of the known surviving 233 copies of Shakespeare’s first folio (the number changes depending on discoveries).[39] By comparison, the largest number of these rare volumes held in a single collection in Britain is 5. The Washington library also has 118 copies of the second, third, and fourth folios, 229 quartos, and about 7,000 other editions of Shakespeare’s works. Of course, Folger—like Adams, Jefferson, Lincoln, Du Bois, and generations of less illustrious Americans—understood well that no accumulation of folios or quartos could give one what is most worth seeking in Shakespeare and what had for three centuries been contributing to America’s well-being. A first folio is like the engrossed copy of the Declaration of Independence. However rare the physical artifact, what is most precious in it, its “Apple of Gold,” is accessible to everyone who is willing to liberate himself from the narrow, conventional prejudices of his own time and place and open his mind to being “wed with truth.”

Whether future generations of Americans will be so open-minded will depend considerably on what kinds of educations they get—the kinds that inspired Lincoln, Folger, Du Bois, and generations of others to seek in Shakespeare’s writings insight into timeless and universal truths about the most important things, or the kind that persuaded Stephen Greenblatt and recent generations of Shakespeare scholars that all such insights are made up. But the “revelation” that Greenblatt experienced in the 70s—that even seemingly “timeless and universal” insights have “a history,” that the things that “seem given are not given, that they’re made up,”—was itself, of course, necessarily “made up.” Greenblatt cannot, from his own point of view, want his revelation to be treated as a “given,” as a “This must be so.” At its best, it will achieve, and take pride in achieving, what Shakespeare allegedly achieved with his art: it will be “malleable,” “available” to other life-worlds, and susceptible to “change” by the passions and rages that animate them, however crazy. It is a revelation that, from its own point of view, must be understood to have a history. It understands itself to emerge from a fleeting and even crazy life-world. It is a product of the prevailing influences of the moment. That is, it is a product of power in one form or another; and, from its own point of view, so is everything else. So it does not claim to offer any firm ground from which to rage against alleged abuses of power by racists, sexists, and colonialists. It is no more a “given” that one should rage against colonialism, racism, and homophobia than that one should rage for them. “Everything includes itself in power.”

The commitment to “change” would seem to move in only one direction. Change as change, if it is going to change, can change into only one thing: permanence. Implicit in Greenblatt’s commitment to change is a movement toward recognizing that what makes Shakespeare’s art “available” to generation after changing generation is not that it is “malleable,” but precisely the opposite, that it is somehow “timeless and universal.” But inquiring students will want to find out for themselves what Shakespeare has to offer. Mrs. Emily Jordan Folger became a Shakespeare scholar in her own right. She sought advice about studying Shakespeare from the renowned Shakespeare scholar Horace Howard Furness, editor of the New Variorum edition of Shakespeare’s works, the most authoritative and reliable edition then in existence. He advised her: “Take Booth’s Reprint of the First Folio, and read a play every day consecutively. At the end of the thirty-seven days you will be in a Shakespearian atmosphere that will astonish you with its novelty and its pleasure, and its profit. Don’t read a single note during the month.”[40] That advice might prove too stern for today’s students. But they might pick up a reliable edition of Shakepeare’s works—say, The Complete Works of Shakespeare, edited by David Bevington in its first or second edition; or The Riverside Shakespeare, in its first or second edition—and, with the help of a few notes, discover a world worth discovering.

*A version of this essay was first published in Education in a Democratic Republic: Essays in Honor of Peter W. Schramm, edited by Christopher Flannery and David Tucker, with an introduction by Roger L. Beckett, Ashbrook Press, 2018.

[1] W.E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk (Chicago: A.C. McClurg & Co., 1903), Ch 6,

[2] William Shakespeare, The Complete Works of Shakespeare, ed. David Bevington (New York: HarperCollins, 1992), Act 1, scene 3, line 455.

[3] Ralph Waldo Emerson, The Complete Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson: Miscellanies [Vol. 11](Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1903), XXIII; “Timeline of the Folger Shakespeare Library,” Folger Shakespeare Library, accessed March 10, 2017, http://folgerpedia.folger.edu/Timeline_of_the_Folger_Shakespeare_Library.

[4] Shakespeare in America: An Anthology from the Revolution to Now, ed. James Shapiro (New York: The Library of America, 2014), 401; Andrea Mays, The Millionaire and the Bard: Henry Folger’s Obsessive Hunt for Shakespeare’s First Folio (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2015).

[5] Aristotle, Metaphysics, 980a.

[6] Patrick J. Keane, Emerson, Romanticism, and Intuitive Reason (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2005), 140.

[7] Emerson went on: “ . . . [It] was not history, courts and affairs that gave him lessons, but he that gave grandeur and prestige to them. There never was a writer who, seeming to draw every hint from outward history, the life of cities and courts, owed them so little. You shall never find in this world the barons or kings he depicted. . . . There are no Warwicks, no Talbots, no Bolingbrokes, no Cardinals, no Henry Fifth, in real Europe, like his. The loyalty and royalty he drew was all his own. The real Elizabeths, Jameses, and Louises were painted sticks before this magician. His birth marked a great wine year, when wonderful grapes ripened in the Vintage of God.”

[8] John Dryden, An Essay of Dramatick Poesie, ed. Jack Lynch (London: Printed for Henry Herringman, 1668), https://andromeda.rutgers.edu/~jlynch/Texts/drampoet.html.

[9] Thomas Jefferson, Letter to Robert Skipwith with a List of Books for a Private Library, 3 August, 1771, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-01-02-0056.

[10] Founding Families: Digital Editions of the Papers of the Winthrops and the Adams’s, ed. C. James Taylor (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 2017), Vol. 2, https://www.masshist.org/publications/apde2/view?id=DJA02d065.

[11] John Adams, The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States: with a Life of the Author, Notes and Illustrations, by his Grandson Charles Francis Adams (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1856), Vol. 6, http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/adams-the-works-of-john-adams-vol-6.

[12] Richard A. Van Orman, “The Bard in the West,” Western Historical Quarterly Vol. 5, No. 1 (Jan., 1974), pp. 29-38, n. 1.

[13] Shakespeare in America, ed. Shapiro, 422.

[14] Esther Cloudman Dunn, Shakespeare in America (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1939), 74.

[15] Lawrence W. Levine, Highbrow/Lowbrow: The Emergence of Cultural Heirarchy in America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990), 16.

[16] James Henry Hackett, Notes, Criticisms, and Correspondence upon Shakespeare’s Plays and Actors (New York: Carleton Publisher, 1863), 191 ff.

[17] Emily Johnson, “Whose Chip is it Anyway?” Monticello.org, last modified May 20, 2015, https://www.monticello.org/site/blog-and-community/posts/whose-chip-it-anyway; That Jefferson did not merely dismiss such relics out of hand is shown in a letter about the new Constitution, which he wrote to John Adams in November 1787. There he wrote, “I think all of the good of this new constitution might have been couched in three or four new articles to be added to the good old venerable fabrick [the Articles of Confederation], which should have been preserved even as a religious relique.” Thomas Jefferson, Letter to John Adams, 13 November 1787, http://www.let.rug.nl/usa/presidents/thomas-jefferson/letters-of-thomas-jefferson/jefl65.php.

[18] Abigail Adams, Letter to George Washington Adams, 7 August 1815, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-03-02-2909.

[19] Levine, Highbrow/Lowbrow, 17-18.

[20] Shakespeare in America, ed. Shapiro, 295.

[21] Van Orman, “The Bard in the West,” 35.

[22] Walt Whitman, “What Lurks Behind Shakspere’s Historical Plays?” Walt Whitman: Complete Poetry and Collected Prose (New York, The Library of America, 1982), 1148 ff.

[23] “Writing—the art of communicating thoughts to the mind, through the eye—is the great invention of the world;” Abraham Lincoln, Second Lecture on Discoveries and Inventions, Collected Works, 9 vols., ed. Roy P. Basler (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 361, http://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/lincoln3/1:87?rgn=div1;view=fulltext.

[24] John Hay, Addresses of John Hay (New York: The Century Company, 1906), 334-335, https://archive.org/stream/addressesofjohnh00inhayj/addressesofjohnh00inhayj_djvu.txt.

[25] Letter to James H. Hackett, August 17, 1863, in The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, ed. Roy P. Basler (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 392-393.

[26] Aristotle, Politics, trans. H. Rackham (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1932), vi.

[27] William Shakespeare, The Tempest, Act 1, scene 2, line 89.

[28] Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life, Vol. 2 (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), 823.

[29] Address to the New Jersey General Assembly at Trenton, New Jersey, February 21, 1861, Roy P. Basler, editor, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (The Abraham Lincoln Association, 1953), Volume 4, 236, http://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/.

[30] Thomas Jefferson, Letter to Henry Lee, May 8, 1825, in Thomas Jefferson: Writings, ed. Merrill D. Peterson (New York: Library of America, 1984), 1500-1501.

[31] Percy Bysshe Shelley, A Defence of Poetry And Other Essays (London: Bradbury and Evans, Printers, Whitefriars, 1840), http://www.gutenberg.org/files/5428/5428-h/5428-h.htm#link2H_4_0010.

[32] Allan Bloom, The Republic of Plato(New York: Basic Books, 1968), 598d-e.

[33] “History of the Folger Shakespeare Library,” Folger Shakespeare Library, accessed March 10, 2017, http://www.folger.edu/history.

[34] Shakespeare in America, ed. Shapiro, 418-419.

[35] The teacher was Raymond Williams; Corydon Ireland, “So that represented my own little rebellion: The literary adventures of Stephen Greenblatt,” Harvard Gazette, last modified June 3, 2014, http://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2014/06/so-that-represented-my-own-little-rebellion/; Mitchell Stephens, “The Professor of Disenchantment (Stephen Greenblatt and the New Historicism),” WestMagazine (San Jose Mercury), last modified March 1, 1992, https://www.nyu.edu/classes/stephens/Greenblatt%20page.htm.

[36] Stephens, “The Professor of Disenchantment.”

[37] Stephens, “The Professor of Disenchanment.”

[38] Ireland, “So that represented my own little rebellion,” (emphasis added).

[39] “Rare Shakespeare First Folio to tour all 50 states, DC, and Puerto Rico in 2016,” Folger Shakespeare Library, last modified February 26, 2015, http://www.folger.edu/sites/default/files/FirstFolioTourSites_FolgerPressRelease3.pdf.

[40] “Shakespeare in American Life,” Folger Shakespeare Library, accessed March 11, 2017, http://www.shakespeareinamericanlife.org/education/everyone/library/origins_2.cfm.